Perhimpunan

Dokter Paru Indonesia

Indonesian Society of Respirology

Organisasi yang mewadahi dan membina para dokter paru atau pulmonologi di Indonesia.

Info Kesehatan Paru

Informasi tentang kesehatan paru dan ilmu penyakit paru.

Berita Organisasi Terbaru

Berita terbaru seputar kegiatan dan perkembangan organisasi.

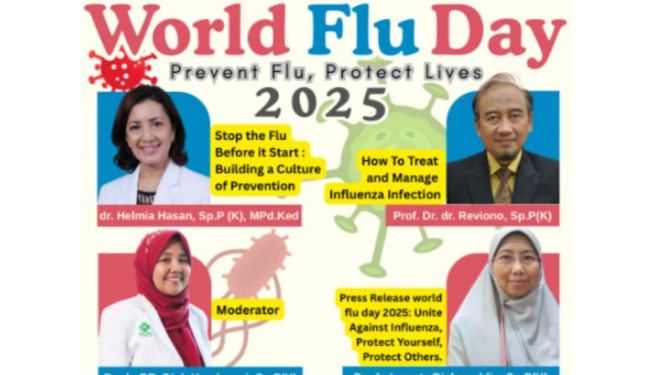

Program dan Kegiatan

Informasi program pendidikan, pelatihan dan kegiatan ilmiah.

Program dan Kegiatan

Program dan kegiatan ini mendukung peningkatan layanan kesehatan paru melalui edukasi, pelatihan, dan kampanye kesadaran bagi tenaga medis dan masyarakat.

Buku PDPI

Kumpulan buku dan pedoman resmi yang disusun oleh Perhimpunan Dokter Paru Indonesia sebagai referensi ilmiah dan panduan praktik bagi tenaga medis.

BERITA PDPI

Informasi terbaru seputar dunia kesehatan dan inovasi medis yang berhubungan dengan kesehatan paru dan pernapasan.

Tentang Kami

Perhimpunan Dokter Paru Indonesia (PDPI)

PDPI merupakan himpunan profesi yang terdiri dari ratusan dokter spesialis paru dan pernapasan (Sp.P) yang bertugas dari Sabang sampai Merauke. Berdiri sejak tahun 1973 dan secara rutin dan berkesinambungan berusaha mengembangkan keilmuan dan pelayanan kesehatan diagnostik maupun terapi yang berkaitan dengan berbagai keadaan pernapasan dan penyakit paru, seperti asma, penyakit paru obstruktif kronik (PPOK), kanker paru dan mediastinum, infeksi paru termasuk tuberkulosis; kedokteran intervensi, pelayanan kesehatan kritis dan gawat darurat; penyakit gangguan tidur (sleep medicine); penyakit paru lingkungan dan upaya pengendalian akibat tembakau; dan penelitian kedokteran translasional.

Kontak Kami

Sekretariat PDPI

- Rumah PDPI Jl. Cipinang Baru Bunder No. 19, Cipinang, Pulogadung, Jakarta 13240

- (021) 22474845

- penguruspusatpdpi@gmail.com

- sekjen_pdpi@ymail.com